|

|

||

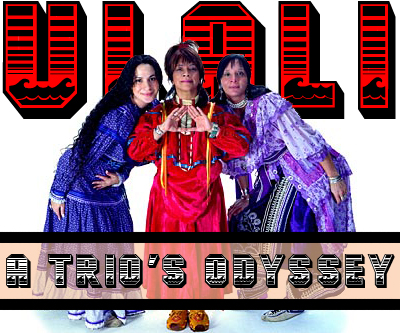

Ulali: A Trio's Odyssey Harmonized song birds Soni Moreno and Pura Fe Crescioni were all ready well dug in to the business of music before the group Ulali hit the airwaves, paying their dues to the music gods with a string of bands and projects for years before fate intervened. “I was recording at the time with my own music and fusion band when I met Soni,” says singer and Ulali founder Pura Fe, “Soni was singing with her friend Martha Wingate and a band, and when I heard them, I thought Soni should be singing with me.” As regulars to the ever growing, transient mass of Indians that wandered through the doors of the American Indian Community House, Soni and Pura Fe’s paths began to cross, leading to a friendship that would first encompass singing together, then forming a new band called Pura Fe. “The group was called Pura Fe because we didn’t have a name and it was sort of like pure faith that we all got together,” says Soni Moreno. “It was Matoaka Little Eagle, Pura Fe, and myself as the female singers, and on drum we had Cochise Andersen, Kenneth Little Hawk, Andy Wounded Knee, and Frank Menusan.” Pura Fe was an eclectic sound with a strong influence of blues, the sound of the Pow Wow drum, and the mixing of the three women’s harmonious voices; the end result being an album titled “One Shield - Blue Walk,” now a collector’s item. After extensive touring, Pura Fe disbanded, leaving Pura Fe and Soni to talk about a new group; one that would showcase their voices without the men in the background or the sound of the large drum. And with the loss of Matoaka Little Eagle, a new female singer would be needed to round out the sound. “I was still in high school at the time Pura Fe and Soni came together,” says Jennifer Kreisberg, Pura Fe’s cousin. “They needed someone and I knew all the parts – I just knew the music, so I came and filled in and it worked out really well.” After graduating from high school and attending three semesters of college, Jennifer dropped out and began singing with Soni and Pura Fe full time. “I was just not enjoying college: I didn’t know what I wanted to do. What was funny was that I excelled at biology, for some reason it came easily – don’t ask me why – but I just really didn’t care for it very much.” At the time Jennifer joined, the group had changed its name from Pura Fe to Pura Fe and Soni, a name that managed to only encompass two thirds of its members, thus making the other third very uncomfortable, and marking the next phase in the evolution of Ulali. ****** For Pura Fe, Jennifer, and Soni, the music god that had silently collected dues for over twenty years manifested itself in the form of a rock legend. Much like the return of Quetzalcoatl or Lono, Robbie Robertson’s arrival marked a period of doubt and change for the group. While Cortez and Cook were ultimately exposed as anything but gods, so far, little has been done to prove otherwise for Robertson, or his influence in bringing Ulali to the attention of the world. 1994 marked eighteen years since Robertson’s departure from one of America’s most influential rock groups, The Band, as well as a return to his Mohawk roots in the form of the documentary, The Native Americans. As producer of the music for the documentary, Robertson traveled across Indian country in search of talented musicians to feature for the show as well as his coinciding album, Music for the Native Americans. During his search, the trio’s demo came across his desk and after recording two tracks from the yet unnamed group, Robertson pressured them to choose a name. The first attempt at a name came as Ladies Choice – a name all three of the ladies agree sounded more like a feminine hygiene product then a proper handle. After non-stop brainstorming, the ladies decided to call home and ask for help. “We called down to North Carolina to one of our friends, Larry Dunmore, who’s really good at language,” explains Jennifer. “He called an elder woman in his tribe and she said ‘why not Ulali?’ and he was like ‘You know, why not Ulali?’ We were told that Ulali was a Tuscarora woman who lived a very long time ago and was known for her beautiful singing. Also, Ulali is a Tuscarora word for a wood thrush.” In Tuscarora, as in many languages, onomatopoeia is used to name the bird based on its singing. The wood thrush’s song varies from “U-La-Li” to “U-La-Lu” as well as a number of other variations too difficult to emulate on paper. In essence, the trio was a set of song birds by very definition of their name, christened for a Tuscaroran musical diva. And with a firm identity, Ulali began their career. ***** Through the release of the film Smoke Signals, the world first came in contact with the public and marketable world of Indian country. And one of the biggest talents to make an impression on the world was the collective voice that is Ulali: the group of symphonic sirens that delivered the final scene of the film as we watched Adam Beach, in a bad wig, throw his father’s ashes into a roaring river. His scream becoming a part of Ulali’s heart piercing cry, Ulali’s lamentation ingraining them as one of the primary voices of Native America. “We ended up doing the music to Smoke Signals – straight up – because of Sherman Alexie,” says Jennifer. Shortly before Smoke Signals, Ulali had worked with the Indigo Girls on an album called Honor The Earth. For Ulali, the project culminated in a promotional benefit concert in New York at which Indian author Sheman Alexie attended. “He remembered the performance and he really wanted us to do a song.” What eventually led to Ulali’s inclusion in the film also reveals a lot about their composition and performance style. With only a clip of the final scene and a day and a half to come up with a new song, Ulali began their task in much the same way many of their songs have come about: improvisation. A jam session consisting of only their voices. “We watched it over and over,” says Soni, “and we were writing as we were watching. And it was Jennifer’s birthday and there was a lot going on and we were all on cappuccinos for most of the night.” After 36 hours, Ulali had written, recorded, and shipped the song to Los Angeles. “Sherman took it as ‘they’re gonna hate it or they’re gonna really like it,’ and at that point the whole process had become pure emotion. I think it’s one of my favorite pieces. It’s really up there with Mahk Jchi.” Only a year before, Ulali had released their debut album Mahk Jchi, and with their own release, their inclusion in Smoke Signals, and their constant touring schedule, the trio looked to be unstoppable, making it evident that Native America was watching the rise of a new breed of artist. They became popular in Europe, their voices were known in America, their cross-over possibilities were clear when their harmonies appeared in the documentary 1 Giant Leap, and their status as musicians palpable after performing at the V-Day benefit at Madison Square Garden; the Olympics in Atlanta and Salt Lake City, and even Woodstock ‘94. Then, there was nothing. **** Soni Moreno manages the gallery at the American Indian Community House at its new location at 11 Broadway; an area of town where nobody uses space heaters or hangs their laundry out to dry. “The first time I ever saw Soni was at a bus stop in New York,” stated Pura Fe, “She had two long, shiny braids to her hips and a see-through, white-lace, tiny top with a leather vest, a pair of big, bell-bottom, hip-hugger jeans, and huge platform shoes.” Soni’s the only member of the group I talked to in person. She’s less extravagantly dressed than how Pura Fe described, but she still maintains a flamboyant and eclectic sense of style. Despite her involvement with Ulali and their still-rigorous touring schedule, she is committed to her job at the Community House, producing events in New Mexico with Emergence Productions, and working on her own personal projects during her personal time. “I think I want to do a little bit of rock and roll,” she tells me, “I want to work with my kids. I write with a couple of people and I sing with another group called Mato.” The week before, Soni blew her voice singing karaoke: Piece of my Heart, and Bonny Raitt are to blame she tells me. What interests me about Soni is that she is an undocumented Indian. She is Mayan, Apache, and Yaqui, but has no papers, no blood-quantum, and no tribal enrollment. What’s interesting, though, is that anywhere she travels in or out of Indian country, she’s accepted. And on top of that, her shining personality and influence through her membership to Ulali means that she’s respected, which bring up lots of the same old questions that have been endlessly tossed back and forth for the last fifty years. “Your number, your paper; that doesn’t make you who you are. This art project I’m doing is all about that. It’s a little kind of autobiography called The Trilogy: No Borders.” It’s called the trilogy because of her family’s relationship to the number three: growing up it was only Soni and her two brothers and today it’s her and her two children. For Soni, it’s an autobiography of the number three consisting of eleven pieces of mixed media with accompanying music and short film. Most days you can find her in the Community House gallery, scurrying between offices, straightening the gift shop, or preparing for the next show. “This is what I love,” she says, “I’ve been a part of this community and this community has been a part of my life for so long that I want to see the transition. I want to be here to nurture and cultivate this next group of people that’s going to come in.” *** For about a week Pura Fe Crescioni and I spoke through email. I never found out how her or her family ended up in New York, and I never got to hear her voice, or the tone, inflections, or tangents that most people employ when speaking person to person. She lives in Seattle, Washington today, and is expecting a total of three album releases this year. “I didn’t plan to have all these CD’s come out at the same time,” typed Pura Fe, “It just happened. Years ago an artist wouldn’t have been able to let that happen, but with all the experiences and promises we, Ulali, have had, and contracts we’ve signed and had to get out of, I managed to stay free of the noose. I didn’t plan it, it just happened. So I’m hoping for a good year.” Besides the three upcoming albums, Pura Fe has released three other albums during her time with Ulali and during her unofficial departure: Caution to the Wind, Follow Your Hearts Desire, and Tuscarora National Blues. “Ulali is taking a break,” says Pura Fe. “We all live far away from each other and it’s really hard to write, rehearse, and so on when we are so far from one another. We’re all going through a transition and need time to rejuvenate and become inspired by life; to begin to feel good about ourselves again. “As Ulali, we know what we are. But we also know that we have to charge our batteries again – we have to take the time to repair. Not turn away, but claim our own feelings, desires, ideas, and thoughts; we need to own our own selves again. We’re women that go through life changes, remember that. A CD will come, but in the meantime, you can enjoy our individual projects. We didn’t quit, but we need to do our own things because we don’t all like the same things. We are more than just Ulali and we love each other deeply. Breaking up isn’t necessarily a negative thing; we grow old and need a break.” As founder of the group, decisions lay heavy on Pura Fe’s shoulders. As one-third member of the group with a new singer, Atuahua Papa, learning her parts, she is now able to continue the pursuit of her solo career unabated. She has documentaries lined up, collaborations looming in the future, and a monster of a work ethic that can allow her to spit out multiple CD’s in a year as opposed to one CD every few. It’s obvious that Pura Fe is immensely talented with a determination to keep singing no matter what, but what will become of our stars, Ulali? And how long will more dues have to be paid before another break the size of the Ulali explosion comes along? “So much in Indian country doesn’t last. It falls apart, and it would be so nice to see something that stands the test of time. But then again, as Indians, I think we’ve done that. Like roaches, we’d be here after a nuclear war, and that’s what I feel we have done.” ** Recently, Jennifer Kreisberg won a Genie Award – the equivalent of an Oscar in Canada – for her song Have Hope, which was featured in the film Unnatural and Accidental. The song will appear on her upcoming album Wa Thye Yeh Rak, which means “She Mixed It” in English. When I reached her by phone at her home in Connecticut, her son had just gone to bed. “Ulali’s trying to put out a live album,” she told me. “We have a few shows that we did last year that we recorded live, and we actually have a lot of songs that we do now that aren’t on our album. We’re definitely not going to break up. We might take a very long hiatus – like a few years – but I think that what all of us are going to find out, and what we may have found out all ready is that you work hard as a group, and a group in Indian country has a certain place. It has a certain place that will always be able to work as Ulali until we’re old women, at least I think, so it would be silly to cut that off.” According to Jennifer, Atahua Papa, a Maori woman from New Zealand, has been tapped to learn all the parts for Ulali’s songs in order to fill in at live shows for absent members starting with Pura Fe’s parts, then moving to Jennifer’s, and finally, Soni’s. “She lives in New York City, so it was easy for me and Soni to work with her.” Both of Jennifer’s parents were music majors at Hart College of Music in New York, where they met before moving to Connecticut. Ranging from the Beatles to Motown, children’s songs to hymns, there was always a lot of singing in the house, and Jennifer’s ear soon began to pick up a sense of harmony. In high school, she found new sounds; John Trudell, Public Enemy, Bob Marley, U2, Buffy St. Marie. Socially driven music, which she attributes to her place in the horoscope: Libra; a group of star children incensed with ideas of fairness; ideas that she continues to incorporate into her life and music. “I think that’s what Ulali stands for,” says Jennifer, “and for me as a solo artist: absolutely.” Besides Jennifer’s solo projects and family responsibilities, she’s decided what she wants to do if she goes back to college: naturopathic medicine with a strong understanding of western science in order to take care of her parents in the future and to treat her family and herself. * I make my way down to the Community House about once a week past hordes of expressionless business men and tourists – transplants from Colorado or California or Michigan – lured by the seductive neon fingers of New York; its endless possibilities and impenetrable skyline. The people I pass have come to New York for the same reasons that we all have. The same reason I came. They’ve heard the hymn of New York in books, music, and movies and pulled out of small town obscurity to live anonymously among the mob in the street. All adherents to the gospel of New York hope that they will find success in their lives in what ever form that takes. Some do it for art, some do it for money, some do it for love. It’s the same for the Indians that make their way down to the Community House with their long-hair and threadbare t-shirts; they arrive in search of their fortunes, but also, camaraderie. They look to find people that remind them of home and cousins and old friends. Things they had to give up to find something that couldn’t be found at home. Some, like Ulali, will find both, and they will be able to call home proudly instead of lying about the wonders of big city life. But even a word like success has its downsides, meanings, and connotations that rest more on social expectations then personal needs. What is important is that one finds success on their own terms; not Americas, not parents, not friends, not peers, but terms that resemble a persons own expectations and dreams. Success has always been what makes you happy, regardless of the background you come from. Something that so few people can actually find, and instead, accept substitutes that mirror the success the rest of Americas bored soul finds comfort in. The success that Ulali found may not have been what they were looking for, but hopefully, when it comes again, it will be what they need. As observers taking part in their story through this article, the only way we can judge success is through our own, personal lenses. What makes us happy? If the success that Soni, Jennifer, and Pura Fe achieve is different than what we desire in our own lives, who are we to judge how other people find happiness? After all, isn’t personal happiness what we’re all searching for? I see Soni almost every time I come in to the Community house, and now, when I see her, it reminds me that for the last two weeks nearly all I have been able to think about is Ulali. How could I write their story with no fixed future? With no clear cut goal that they are currently working toward as a group? Their past is easy to sum up – the curse lies in trying to find meaning in their actions now. I have heard their music, seen their performances, spoken with them, agonized over them in order to put an end to this article, but I have nothing, and I am afraid that there is nothing more to say. Perhaps we are nothing more than fellow countrymen in Native America, in search of a story that makes sense to us; in search of a story that may not have an ending. |

||

|

|

||