|

|

||

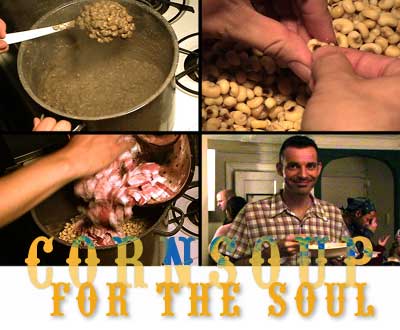

When I was fifteen years old my grandmother taught me how to make corn soup. I was able to use my newfound skill to help my family make ends meet. My mother and I used to pool our bits of change together to buy the ingredients. A quart of dry corn can be bought from a nearby farmer for four dollars. The ashes I got for free from my uncle. The salt pork and kidney beans were just couple of dollars. We would start preparing our soup early in the morning. We would finish just before dinnertime and then we would go door to door selling our soup for four dollars a quart. When all was said and done, we amassed about fifty dollars. We would go to the supermarket and buy food staples to get us through to the next paycheck. Sometimes, my mother and I would spend half our earnings and we’d go to play bingo at the nearby church in the hopes of winning the two hundred dollar jackpot. Even if we lost all our money, we knew we were seven dollars away from earning another fifty dollars by selling corn soup. Although I have been living in New York City for almost twenty years, I can still make an excellent batch of corn soup. Deep down, I feel like a Native American food ambassador and it is my duty to introduce the outside world to our Native cuisine. Although corn soup has only four ingredients: Iroquois white corn, wood ash, salt pork and dry kidney beans, its preparation involves a complex process involving the corn and wood ashes. Iroquois white corn is not like the typical sweet corn we enjoy today. The kernels of white corn are much bigger than sweet corn and its color is not nearly as yellow. It is grown in fields and is harvested. The husks are pulled back away from the ear and allowed to air dry. Once thoroughly dried, the kernels are removed from the husk and placed in an airtight container for future use. Each kernel is encased in an inedible hull, which must be removed by boiling the corn in a water and wood ash mixture. This hull removal process is known as “cleaning” the corn. Wood ash is not an ingredient one can buy in a supermarket. I attain my ashes from my uncle who still heats his home with a wood burning stove. It is important that the ashes are the result of burning a hard wood like red oak. These ashes are sifted to separate the ashes from any unburned wood remnants. When making corn soup, the first step is to place equal parts corn and sifted ash into a pot. It is important to add enough water to allow the mixture to boil. Adding too much water will not “clean” the corn sufficiently. Not adding enough water increases the possibility of burning the corn. Without giving a scientific explanation, the ash and water mixture creates a weak lye solution. Once this solution has boiled for thirty minutes, the corn is rinsed of all ashes and is then soaked in cold water. During the boiling process, the hulls turn black. The objective is to remove these black hulls by gently rubbing the kernels between both hands. This process is the most time consuming since not all the hulls will come off easily. For those stubborn hulls, the individual kernel must be picked up and flicked off with your thumbnail. This process continues until the white corn is hull free. Depending on the amount of corn boiled and the quality of the ashes, it can take up to three or more hours to clean the corn. It’s not uncommon to have sore neck and shoulder muscles from being hunched over the sink for hours. Having the help of a family member or friend makes cleaning corn more fun than work. Getting wrapped up in conversation and gossip while cleaning corn makes the time fly. Once the corn is cleaned, the remainder of the recipe is easy. Slice the salt pork into small cubes and place them along with the cleaned corn and water into a pot and bring to boil. The corn will take at least a couple of hours to cook. Its important to coordinate adding the kidney beans so they will finish cooking at the same time as the corn. When the corn and beans have finished cooking, it will be ready to serve to your guests. Serving fry bread with corn soup makes the meal complete. Back home, fry bread is referred as “ghost bread” or “spook buns”. In November of 2001 I invited some friends and strangers to my East Village apartment for my first corn soup party. The invitation read: “You are cordially invited to a corn soup party. Corn soup is a traditional Iroquois Indian delicacy. It can take up to 10 hours to prepare. Ingredients are Iroquois white corn, wood ash, kidney beans and salt pork. Ghost bread will also be served.” I imagined a room full of brave souls willing to taste corn soup for the first time. I knew having wood ash listed as an ingredient might conjure up some strange ideas in my guests’ heads, so I decided to screen a short video presentation showing how corn soup is prepared. A couple days before the party, I borrowed a friend’s mini DV camera. I meticulously staged the camera angles for each phase of preparation. I then spent the next thirty-six hours editing the footage on my computer. In the end, I had a sixteen-minute rough but informational video presentation. Needless to say, my guests enjoyed the video presentation along with some delicious corn soup. I have had three corn soup parties since then and each one was a success. Through the screenings of the video I realized the power of being able to document the Native experience. The Native way of live prior to film and video can only be experienced through still photography and books. One can only imagine what it would have been like to be able to watch our ancestors talk to us through film and video. I believe their teachings would have had a more profuound impact on the Native community today. It may be too late to document their way of life, but it’s not too late to preserve ours, for one day we will be the ancestors to the Native American people of the future. Terry Jones, Seneca Nation, Wolf Clan, lives in New York City and is working as a co-producer on his first feature documentary film entitled “Casino Nation”, which is partially funded by Native American Public Telecommunications (AAPT) and the Eva and Lucius Eastman Fund. “Casino Nation” is scheduled for release in the Fall of 2005. Image by Patrick Tafoya |

||

|

|

||